After Years of Gains, Women Bore Brunt of Pandemic-Related Layoffs

In the fourth quarter of 2019, the female share of total employment hit 50% for only the second time in history (the first being in 2009-10). From this peak, women accounted for nearly 55% of total job losses during the initial wave of COVID-19 pandemic layoffs and the female share of total employment fell to 49.1% by May 2020. Women recovered jobs at a faster pace than men in the subsequent months and today female employment has rebounded to 49.7% of the total.

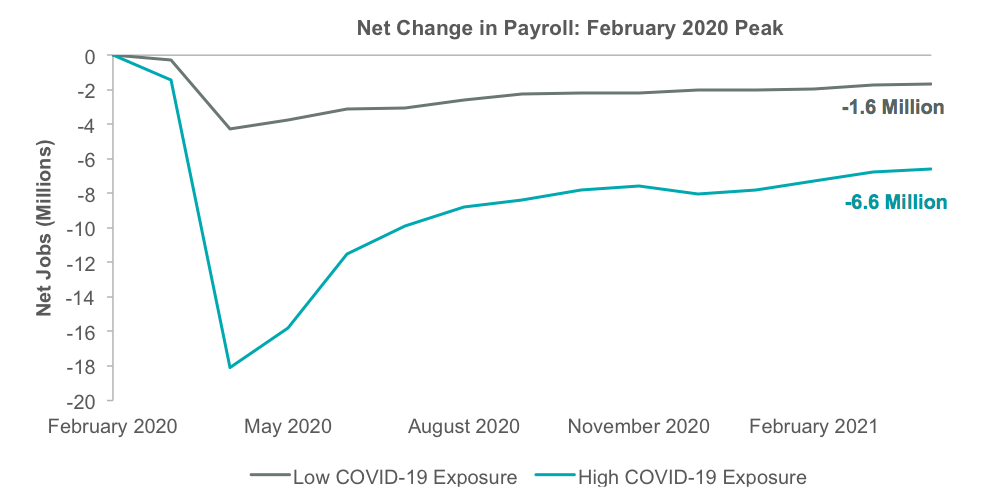

One less-explored potential reason for this dynamic is the large share of female workers in industries most-impacted by the pandemic. Leveraging academic research, we classified industries as having high or low COVID-19 exposure based on 1) ability to work remotely, 2) essentialness, and 3) impact of supply and/or demand shocks from COVID-19. Unsurprisingly, the vast majority of layoffs were concentrated in high exposure industries such as leisure/hospitality and retail. Those industries have also seen a greater subsequent recovery.

Exhibit 1: A Tale of Two Labor Markets

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford

What is surprising, however, is before COVID-19 hit, females accounted for 58% of employment across high-exposure industries and just 38% of the workforce in low-exposure industries (such as manufacturing and technology). Put differently, women accounted for a greater share of jobs in the industries that were harder hit by the pandemic, and a smaller share in industries that were more insulated. Interestingly, women actually lost more than their pre-pandemic share of jobs within high-exposure industries but lost fewer than their pre-pandemic share of jobs within low-exposure industries.

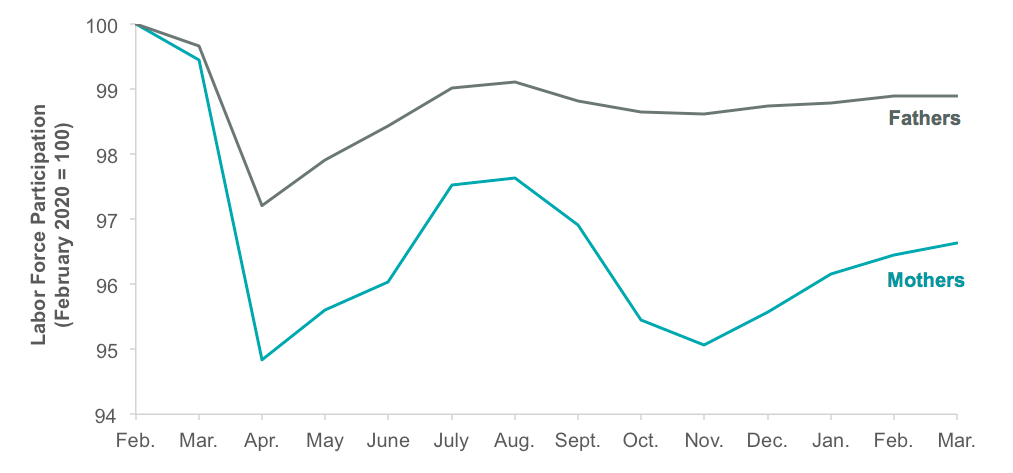

There are other reasons why women were more impacted than men by the pandemic within the labour market. Researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco recently publish a paper “Parents in a Pandemic Labor Market” that found a pandemic divergence in labour force participation (those who have jobs plus those actively seeking jobs) between fathers and mothers. Specifically, labour force participation had shrunk by 1.1% for fathers during the pandemic compared to a 3.4% decline for mothers. While many mothers were returning to the labour force during the spring and summer of 2020, a large drop off occurred in the fall when school resumed (virtually for many) as shown in Exhibit 2. Approximately one-third of K-12 students are still attending hybrid or virtual-only school today, according to data aggregator Burbio.

Exhibit 2: Labor Force Participation During COVID-19 by Parental Status

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

This would support the notion that childcare responsibilities (including remote-learning supervision) have been falling to women more than men. Some women have had to make the difficult choice between a job and taking care of their children due to the pandemic, and this has weighed on female employment levels. In fact, 33% of non-working women between the ages of 25 and 44 cited childcare demands as the primary reason for their departure from the labour force, compared with just 12% of men according to the Census Bureau. The aforementioned research paper also finds a strong correlation between female employment trends and flexible working hours. Specifically, industries with a higher share of jobs with flexible hours saw fewer female job losses, while industries with a lower share of flexible hour jobs saw greater female job losses. This dynamic was less pronounced for men.

Pandemic Silver Lining – Remote Work Gaining Acceptance

We believe this finding is encouraging, given an increasing post-pandemic shift towards greater workplace flexibility. Further, the normalization of these practices should bode well for female employment. Prior to the pandemic, only 7% of the U.S. workforce had access to remote-work policies and related flexibility benefits according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. During the peak of stay-at-home last spring, it was estimated that nearly 50% of Americans were working remotely, and many companies are planning on keeping partial or even full work-from-home policies once COVID-19 subsides.

With more Americans likely to work remotely part of the time in the future, perceptions around remote work are also likely to change. According to Ellen Ernst Kossek, a Purdue expert on inclusive organizations, “[Pre-COVID] research shows that if you’re using telework and flexibility to finish a project late at night, managers love you; if you’re using it for family or personal reasons, they stigmatize you and think you’re not career-oriented.” With many seeing just how productive they can be, the stigma of remote work is likely to be lessened in the future.

In recent months, ClearBridge has been actively engaging companies on workplace flexibility, encouraging them to make the most of this opportunity for change. While we recognize there is no one-size fits all approach, we ask all companies to think through the many impacts a partial shift to remote work could have on their workforce. Some topics we highlight with management teams are the impact of remote work on newer employees, mentorship and culture, and performance evaluations for remote workers. We believe companies that take a holistic and thoughtful approach to remote work can have a positive impact on their current workforce and attract more talent, particularly women and under-represented groups.

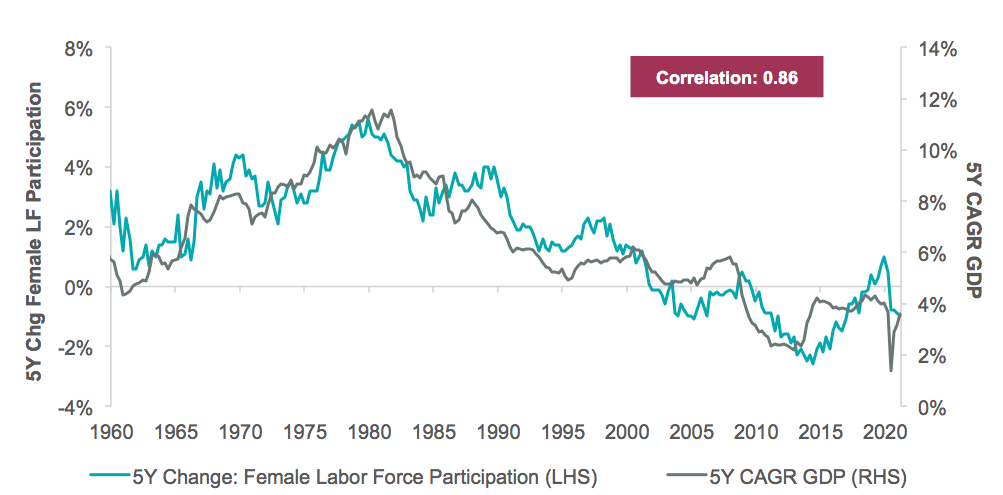

This bodes well for female employment in the future, and for GDP growth more broadly. If more companies offer remote and flexible work and there is less of a negative connotation associated with these benefits, a common reason many mothers leave the workforce will be eliminated. This should allow for more women to participate in the labour force, supporting faster GDP growth over time. Historically, there has been a strong relationship between changes in female labour force participation and trend GDP over the intermediate term (five years).

Exhibit 3: Female Labor Force Participation Correlates with Economic Growth

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.

In the near term, female labour force participation trends could also support more accommodative monetary policy. Last summer, the Federal Reserve concluded a review of their monetary policy framework, revising their stated goals to “emphasizes that maximum employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal. This change reflects our appreciation for the benefits of a strong labour market, particularly for many in low- and moderate-income communities.” In effect, this means that the Fed is likely to look beyond the headline unemployment rate when setting monetary policy in the coming years so long as inflation does not run away.

While the unemployment rate has recovered to 6.1%, it would be 7.2% if the female labour force had simply remained constant through the pandemic instead of shrinking by nearly 2 million. When setting policy, the Federal Reserve is likely to consider what a “normalized” unemployment rate looks like. Depending on the rate of women re-entering the workforce, the Fed could maintain easier monetary policy deeper into the economic cycle relative to history.