The global pandemic highlighted that many communities around the world lack the necessary facilities—things like accessible health care facilities and affordable housing—to combat threats like COVID-19 effectively.

Vibrant health care and education facilities, social housing, and buildings for civic services are often the bedrock of healthy and resilient communities. These social-purpose structures can contribute to economic growth and social cohesion, while providing essential services. Unfortunately, such facilities are underfunded in many countries. Better social infrastructure is needed to prepare for future global emergencies.

Public funding shortfall

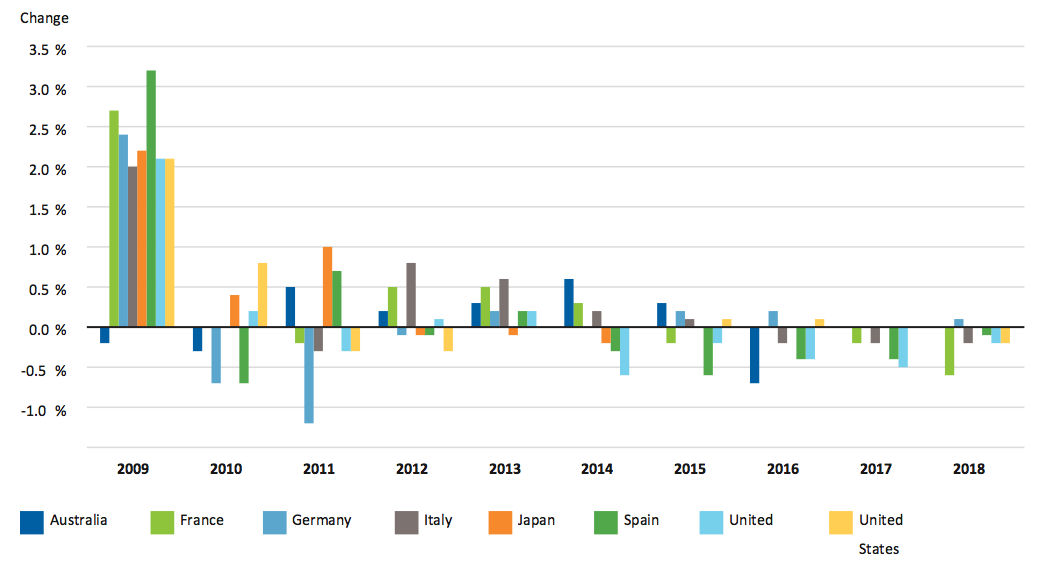

Public investments in social infrastructure dropped sharply after the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis, when austerity policies stifled capital flows, as seen in Exhibit 1.

Austerity’s Global Impact on Public Investments in Social Sectors

Exhibit 1: Social expenditure as percent of GDP in OECD countries, year-over-year change (USD)* (2009–2018)

Sources: Franklin Templeton, OECD, Macrobond. As of November 2020.

Sources: Franklin Templeton, OECD, Macrobond. As of November 2020.

*Note: Australia did not report numbers 2017–2018; Japan did not report numbers 2016–2018.

A 2018 report from the High-Level Task Force on Investing in Social Infrastructure in Europe found the annual investment gap in this space is estimated to be at least €142 billion (US$167.7 billion).

Demographic changes such as aging populations also present a headwind for social infrastructure. In Europe, the share of people aged 65+ is projected to increase from 18.9% in 2015 to 29% in 2060. In Japan, where 28% of the population was 65+ in 2019, there are significant shortfalls in social infrastructure investments. The Asian Development Bank estimated in 2016 that Japan needs to invest ¥10.3 trillion–13.5 trillion to meet demand through 2030 for social infrastructure construction, rehabilitation, replacement and operations.

As countries move past COVID-19, the lack of government investment in social infrastructure is likely to worsen. Debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios for governments across the world are enormous. The International Monetary Fund reports gross government debt in “wealthy countries” will rise by US$6 trillion to US$66 trillion at the end of 2020 (from 105% of GDP to 122%). In developing economies, the World Bank estimated debt hit a record US$55 trillion in 2018.

Need for private capital

Public spending shortfalls plus a magnified need post-pandemic are creating opportunities for private capital investments into social infrastructure. Fortunately, institutional investor interest in impact-focused investment in real estate was growing prior to COVID-19. Most impact investors expect to maintain or boost their commitments to impact investing this year, according to a survey by the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN). Also, a 2020 Preqin survey showed 61% of investors expected impact investing to become more integral in the next three years. With US$8 trillion in assets managed by private capital firms as of September 2019, there’s ample opportunity for private investors to play a leading role in the wake of COVID-19.

Do well by doing good

Social infrastructure is an important, institutional-scale opportunity for private investors to align portfolios with societal benefits and achieve competitive financial performance. In our experience, social infrastructure investments in real estate typically offer predictable returns and tend to be less exposed to market and systemic risks.

These investments may also be less correlated to broader market indexes and other commercial real estate investments. The lower correlation is driven by security of income. Services provided by social infrastructure tenants are often essential, making them less exposed to market volatility. Therefore, they’re less dependent on day-to-day economic activities in the immediate vicinity.

This can underpin rental income certainty in times of distress. For example, immediately after the pandemic started, real estate valuers placed an uncertainty clause on all valuations. This was eventually lifted for real estate sectors with steady income, such as social infrastructure, while more traditional commercial sectors retained these caveats due to higher uncertainty.

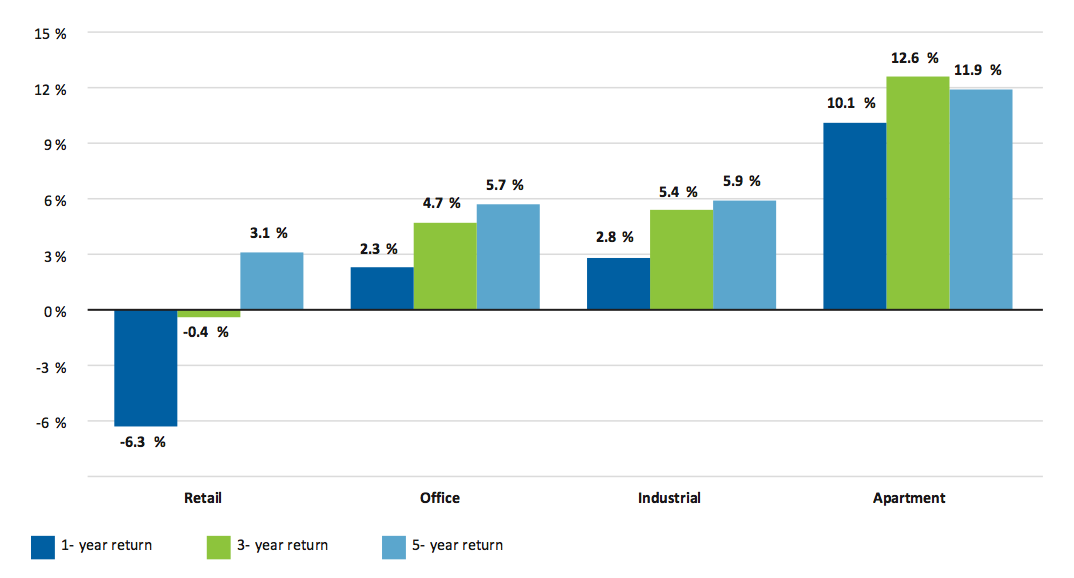

In the U.S., investor demand fell significantly for brick-and-mortar retail (see Exhibit 2). On the contrary, essential assets like health care facilities and education did relatively well. For example, by the end of 2020 in Europe, our strategy saw a near 100% rent collection from tenants in our social infrastructure properties.

COVID-19 Headwinds Weighed on U.S. Retail Real Estate Performance in 2020

Exhibit 2: National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries (NCREIF) Index annualized total returns by sector (USD)

Sources: Franklin Templeton, NCREIF, Macrobond. Indexes are unmanaged, and one cannot invest directly in an index. They do not reflect any fees, expenses or sales charges. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

Sources: Franklin Templeton, NCREIF, Macrobond. Indexes are unmanaged, and one cannot invest directly in an index. They do not reflect any fees, expenses or sales charges. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

The GIIN’s most recent annual survey of impact investors reports the average internal gross rate of return on realized impact investments in real assets (not only real estate) is 13% in developed markets and 8% in emerging markets for market rate investors.

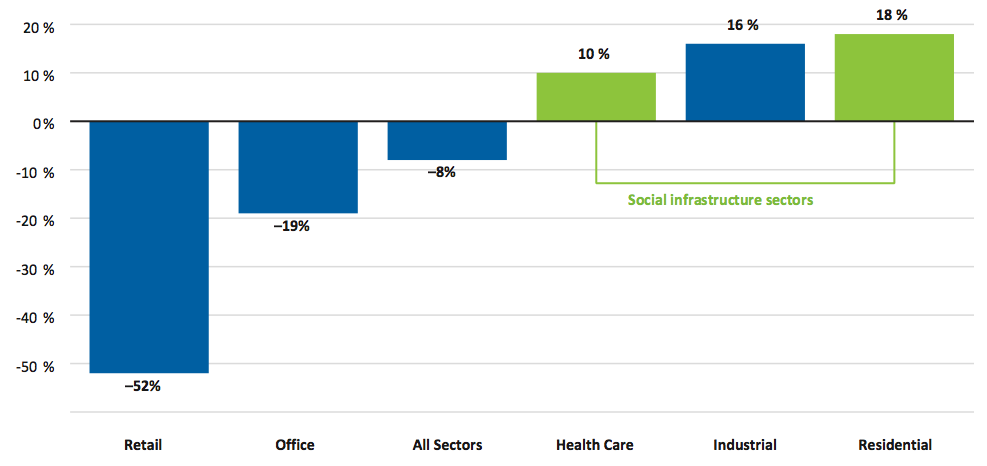

The same survey found that asset allocations to real assets increased 21% between 2015 and 2019. Also, there are data about the resilience of social infrastructure versus commercial real estate assets. Again, focusing on Europe, if we consider real estate investment trusts’ (REITs)** share prices during the very volatile market period of January – July 2020 as a proxy, we can see in Exhibit 3 that social infrastructure sectors increased, while mainstream commercial sectors dropped as much as 50%.

Social Infrastructure Investments Showed Resiliency Against Pandemic Headwinds

Exhibit 3: European REITs: A proxy for social infrastructure performance (January 1 – July 30, 2020)

Source: BNP Research. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

Source: BNP Research. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

A bright future

Investing in social infrastructure with a focus on impact can yield not only market rate returns, it can also create financial resiliency that improves financial results. Fluctuations in other sectors during the pandemic will likely increase institutional investor interest in income-producing real estate whose tenants’ ability to pay rent is less correlated to economic activity. Depending on the severity of COVID-19’s economic fallout, there may be increased sale and leaseback opportunities, as cash-strapped municipalities look to raise funds by selling properties on their balance sheets.

The pandemic emphasized the importance of resilient social infrastructure as well as sustainable communities; it also created more demand for impact-focused capital. The need for better and sufficiently funded social infrastructure is a global phenomenon that now has worldwide attention.