The imperative to reach our net-zero goals is dominating investor conversations these days, and rightly so. Climate change is arguably the greatest threat our society faces. I say “arguably” because the severity of yet another global crisis is quickly gaining recognition as potentially a more direct, more imminent threat, and will undoubtedly begin to loom large in the ESG conversation. That’s the biodiversity crisis.

Aside from the feedback loop these two issues share (accelerated climate change will increase biodiversity loss and increasing biodiversity loss will hinder our ability to mitigate climate-related risks), they have this in common as well: both are insurmountable unless we embrace the principles of circularity.

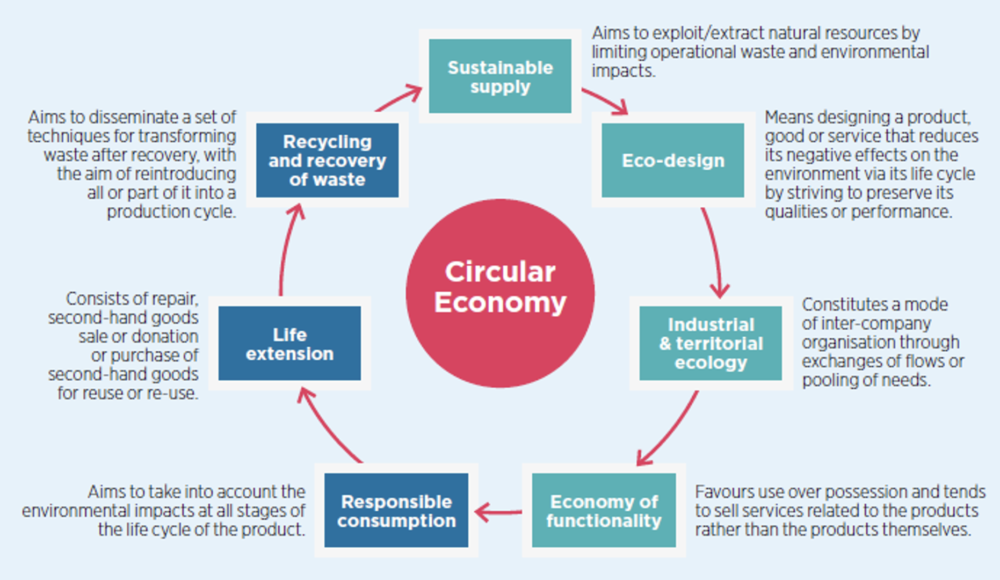

The concept of circularity is not complicated. There are three basic principles: eliminate waste and pollution, keep products and materials in use, and regenerate natural systems. They are the principles that govern the natural world.

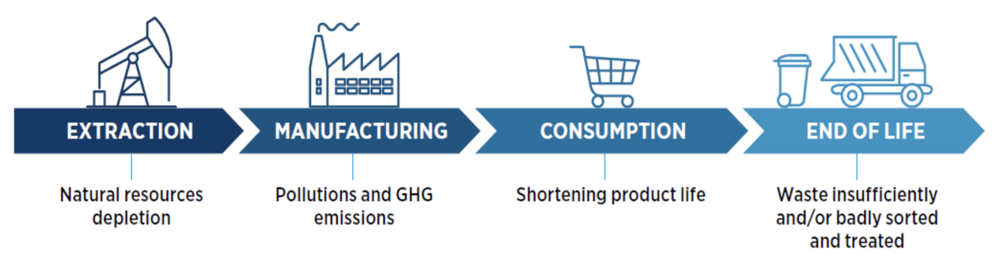

The problem is that our current economic model is largely linear. We harvest a natural resource, we build something with it, and when we’re done with that something, we throw it away. The exceptions to this model tend to prove the rule: most of the products we create are destined for a landfill or an incinerator, or are scattered in the environment as pollution. Think proliferation of ocean plastics, where the expectation is that by 2050, we’ll have more plastic in our oceans than fish. If anyone questioned whether we really are in a biodiversity crisis, that data point alone should erase all doubt.

From an economic perspective, the value at the end of a product’s linear life is nil. More accurately, it is a negative value, since there is usually a cost associated with proper disposal. All the value that was embedded in the product—from extraction to design to manufacturing—disappears. A circular economic model involves rethinking the design of products and their components to reduce resource consumption and the use of harmful chemicals, keeping them at their highest value for the longest period of time through durability, reuse, and repairability, and ultimately, regenerating natural capital. According to the Expert Panel on the Circular Economy in Canada, our economy today is only 6.1% circular. We have a long way to go.

Our approach to addressing the risks of climate change and biodiversity has also been linear, an unconscious extension of our current “take-make-dispose” economy. Look at the drive to decarbonize our energy system and ditch fossil fuels for renewables. This approach doesn’t deviate much from business-as-usual—we’ve just replaced the inputs. No doubt this familiarity is what makes the approach appealing. Without underestimating the vast amount of innovation that has been applied to date, we must acknowledge that innovation has taken place within the confines of an economic model we understand and feel comfortable with.

Amazon offers a case study. The company has a goal of carbon neutral delivery by 2030, and its recent deal with electric truck maker Rivian for 100,000 vans represents just the start of that transformation. Almost all the major car makers see where this is going, with many pledging 100% zero emission vehicles over the next 15 years. Similarly, the drive to decarbonize our electricity grids via a switch to renewables is a core commitment for corporations and governments alike. On the surface, these commitments and targets show excellent progress, and we need them. But the thinking behind them remains tied to the linear economic model, and that’s what needs to evolve.

According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a group focused on building a circular economy, the decarbonization of our energy system will only get us 55% of the way to meeting our goal of net zero by 2050. The other 45% is linked to embedded carbon in the production of materials, products, food, and the management of land. In other words, absent a change in the way we produce things, even a 100% carbon-free grid and all zero-emission vehicles will only get us part of the way there. Looking at Amazon again, what if the company became a conduit for repair and reuse, enabling consumers to extend a product’s lifespan? What if they went beyond the consideration of their own packaging, which is important, to address the upstream impacts and end-of-life plans for the products they ship? What if the company made a commitment not just to net-zero emissions, but to zero waste? Amazon is taking steps in that direction, and is now a member of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. This is a good thing.

A circular economic model might get forced upon us anyway, as our linear decarbonization push is already showing cracks in the system due to resource constraints. The shift to electric vehicles, large-scale energy storage, solar and wind farms, and the growth of the digital economy in general, represents an exponential growth in demand for key minerals. According to the International Energy Agency, a typical electric car requires six times the mineral resources of a conventional car; an onshore wind farm requires nine times the mineral resources of a gas-fired plant. Under the IEA’s Sustainable Development Scenario, lithium demand grows by 40 times, graphite, cobalt and nickel by 25 times, and copper demand more than doubles.

The implications for biodiversity, water security, and Indigenous and community rights due to unrestrained growth in mining to meet this demand should be enough to make us rethink our approach. But even if we were willing to relive the mistakes of the past, it is doubtful we could meet this demand through mining alone. Resource availability will eventually stop us cold. The hard truth of supply and demand points to circularity.

A significant challenge for the investment community is the nebulous nature of the circular economy—it can’t be boiled down to a simple metric like tonnes of CO2 emissions. Moreover, it shares some of the systems-level challenges that have proved so hard for investors to address elsewhere. The promise of the circular economy requires systemic change, from government policies and regulations to industry standard-setting to the creation of a circular business ecosystem. Investors have struggled to address systemic issues to date, now climate change is forcing systems-thinking on us, so perhaps the timing is right.

Despite inherent challenges, circularity does offer business opportunity. According to Accenture, transition to a circular economy could generate US$4.5 trillion in annual economic output by 2030. A study by the United Nations Environmental Programme Finance Initiative of 222 European companies across 14 industries found that the more circular a company becomes, the lower its risk of default on debt over both a one- and five-year time horizon. A circular economy plays both offense and defence. So where to start?

Having the right metrics would help, but if we haven’t hit ESG-framework fatigue yet, surely we’re close. This might not be the best time to suggest we create a “Taskforce for Circularity-Related Financial Disclosures” (trademark infringements alone should warn us off). But I don’t think we need to.

Thankfully, the language of the circular economy lends itself well to the world of ESG. It is all about material flows, resource and energy inputs, supply chain risks, and business model innovation. As we move toward standardization of ESG frameworks (hello International Sustainability Standards Board), investors need to ensure that circularity metrics are front and centre. A natural ally on this front should be the banking sector. In the push to align their lending portfolios and financial products with a net-zero future, investors should be asking banks to actively measure, disclose, and set targets for the circular economy. We should ensure that financial sector commitments to drive the growth of low-carbon technology should also be pushing for these growth industries to embrace circularity.

Plastics is another area that is ripe for circular economy engagement. The Canada Plastics Pact is a momentous development that investors should be embracing and encouraging their portfolio companies to join. The CPP is a multi-stakeholder collaboration that brings businesses, government, NGOs, and other key actors in the plastics value chain together to work toward achieving an actionable set of 2025 targets, such as raising the rate of plastics recycling from today’s anemic 9% to 50%; achieving 30% recycled content across all plastic packaging; and, ensuring 100% of plastic packaging is designed to be reusable, recyclable or compostable. Investors should be encouraging their portfolio companies to join the CPP in the interests of creating the critical mass required to drive systems-level change.

There are many more opportunities to start embedding the concept of circularity into our thinking. Circular Economy Leadership Canada provides thought leadership, technical expertise, and collaborative platforms to accelerate the transition to a circular economy in Canada, and is a great resource we all should use and support. Circularity is a nascent topic for investment and engagement, but one that is entirely aligned with the push to net zero and the urgency of reversing biodiversity loss. If you were wondering why many of the net-zero and biodiversity commitments floating around feel like they are missing something, they are—circularity. It’s something we haven’t been talking enough about, but we really need to start.

RIA Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the Responsible Investment Association (RIA). The RIA does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee any of the claims made by the authors. This article is intended as general information and not investment advice. We recommend consulting with a qualified advisor or investment professional prior to making any investment or investment-related decision.