As responsible investment (RI) continues to grow and evolve at a rapid pace, it is important for investment advisors to stay abreast of key trends and leading practices in the field. Of course, that is easier said than done in a pandemic world that has been characterized by chronic stress and nonstop Zoom meetings — especially when the RI market is evolving so quickly.

To help you stay informed in this fast-moving market, this article provides a quick overview of three big issues in RI that every advisor should know about: stewardship, impact measurement and net zero.

Investment stewardship

The concept of stewardship is gaining prominence among investors in Canada and globally, but what exactly does it mean in practice? While some market participants use the terms “stewardship” and “engagement” interchangeably, leading researchers and practitioners point out that good stewardship is much broader than shareholder engagement alone.

A 2020 report from KKS Advisors, a consultancy led by Harvard professor George Serafeim, stated that “stewardship reflects the role of investors as ‘stewards’ of the assets entrusted to them by their clients and the responsibility of investment professionals to carefully protect and enhance the value of those assets. It embodies the notion that investors are influential market players who have the power to shape markets, enhance governance and address market risks and opportunities affecting the health of the economy.”

Upon analyzing the stewardship practices of 40 of the world’s largest institutional investors, KKS Advisors concluded that stewardship has seven practical components:

- Influence – Leveraging investors’ position within the financial system to drive a sustainable economy; for example, by raising ESG standards and promoting effective policies and regulations.

- Engagement – Proactive dialogue with companies on ESG issues.

- Voting – Communicating and exercising shareholder rights and expectations.

- Promoting disclosure – Encouraging high-quality disclosure of ESG information.

- Monitoring – Actively monitoring ESG performance and new regulations.

- Collaboration – Participating in collective action and coordinating with peers to maximize impact.

- Education – A commitment to internal ESG training and development.

Advisors who are interested in stewardship of their clients’ assets can use this list as a point of reference when examining asset management firms.

Impact measurement

Impact investing is also gaining prominence in the asset management industry. The Global Impact Investing Network defines impact investing as “investments made with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” The key components here are intentionality and measurement. If positive impacts are not intentional and measurable, then we are not talking about an impact investment.

In the context of rising investor demand for positive impact and growing concerns about greenwashing, it is vitally important for fund managers to measure and report on the positive impacts that their clients’ assets are generating. The importance of credible impact measurement is compounded by the fact that we are seeing a growing number of public equity funds marketed as impact investments.

While there are numerous credible impact measurement frameworks on the market, there is no global standard across asset classes. This can make it challenging for investors and advisors to compare impact investments. As a result, the Impact Management Project (IMP) is seeking to build a global consensus on how to measure, manage and report the impacts of an investment. Here in Canada, the IMP has partnered with Rally Assets on their flagship education project called Impact Frontiers, which seeks to build the capacity of investment managers to integrate impact and financial management. These projects will take some time to play out, but given the weight behind IMP, whose advisors include PWC, KPMG, UBS, Bank of America, Ford Foundation and Dutch pension fund PGGM, among others, we can expect to see some level of convergence in the next few years.

In the meantime, fund managers should make use of the most credible tools and methods available to measure and report their positive impacts. Failure to do so could exacerbate concerns about greenwashing in the market. Advisors who want to see impact metrics from fund managers should communicate their expectations to the manager.

Net zero

You have likely seen headlines about “net zero” popping up in your newsfeed. Here’s why it’s a big deal right now in the investment industry.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a United Nations science agency, has reported that in order to avoid catastrophic impacts from climate change, we must limit the average global temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C above the preindustrial era. To achieve this target, global carbon emissions must decline by about 45% relative to 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net-zero by approximately 2050.

Governments around the world, including Canada, are pledging to reduce emissions in alignment with these targets. However, meeting these commitments will require a massive transition of the global energy system, creating risks and opportunities across sectors. These transition-driven risks are compounded by the physical risks flowing from a changing planet.

As a result, many companies and institutional investors are now making pledges to align their business and investment practices with net zero emissions. These commitments send a signal to the market that the business intends to manage the risks and capitalize on the opportunities of a transition to a low-carbon economy.

Conclusion

Stewardship and impact investing are two of the most important strategies available to investors who are interested in achieving net zero emissions. That’s because stewardship can help move companies toward more sustainable outcomes, and impact investing can help move capital toward industries, companies and projects that help drive down emissions. The key is that the positive impacts need to be measurable. If they are not, then it’s not clear that the needle is moving.

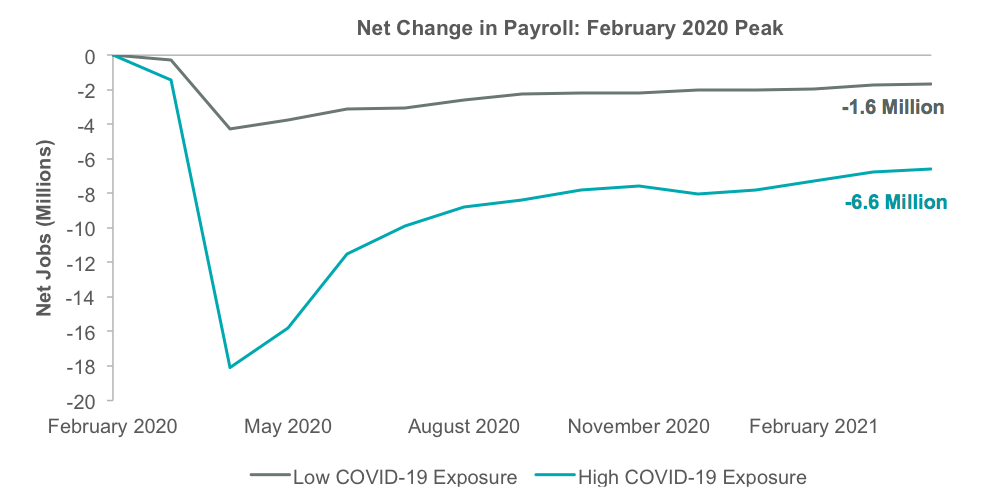

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford

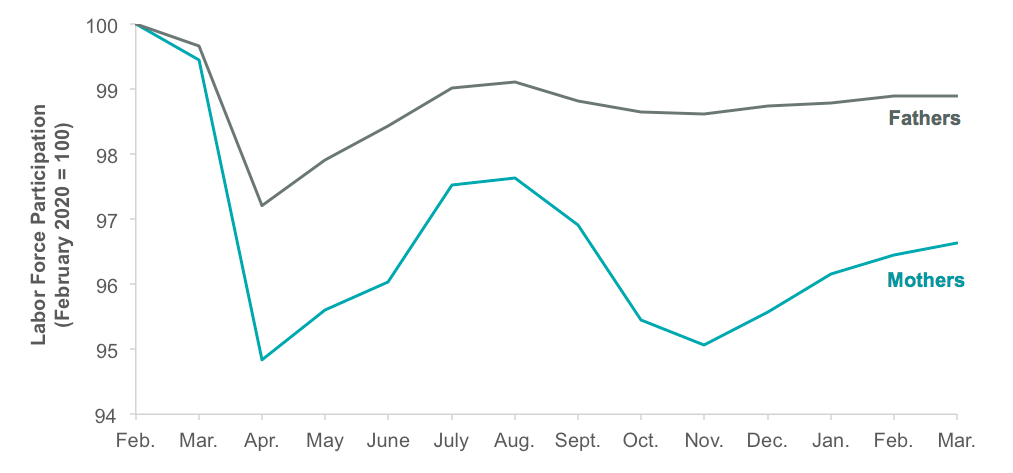

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

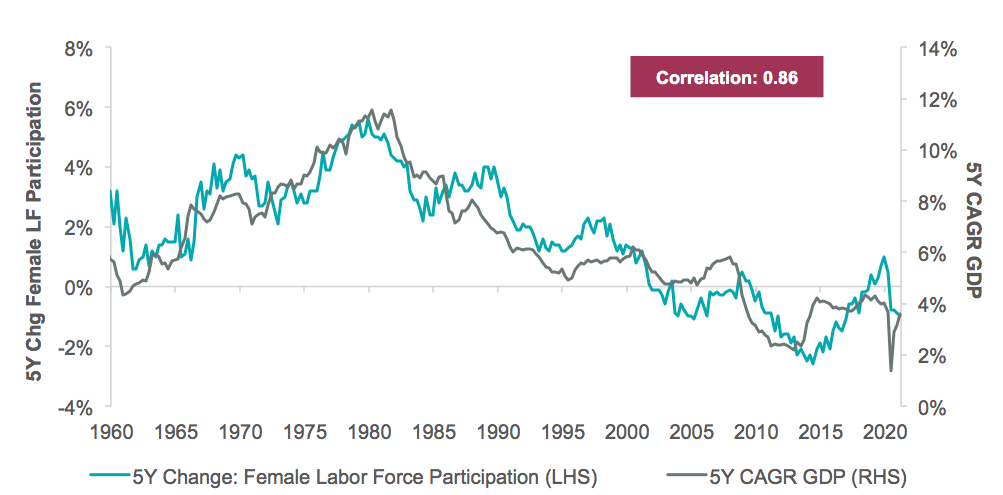

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.

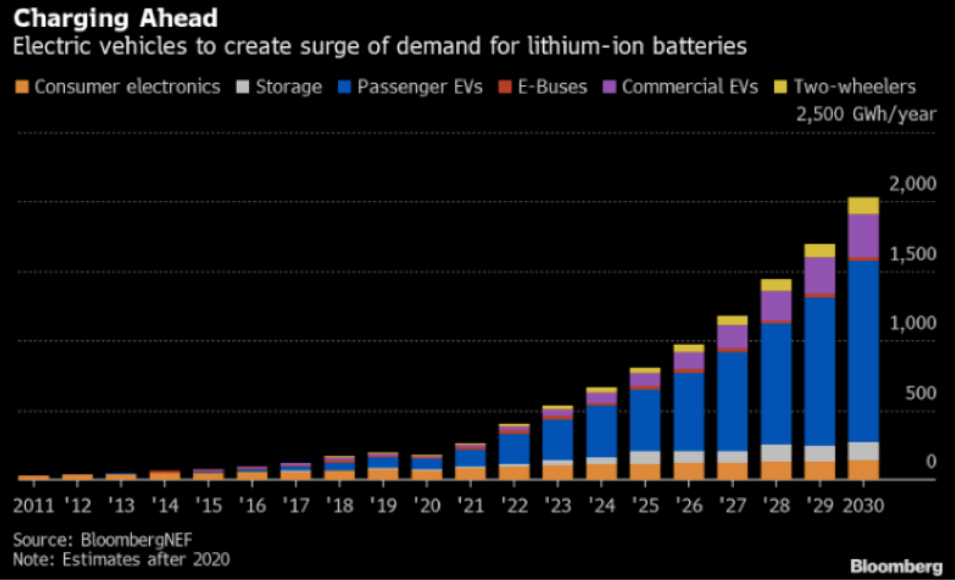

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, as of March 13, 2021

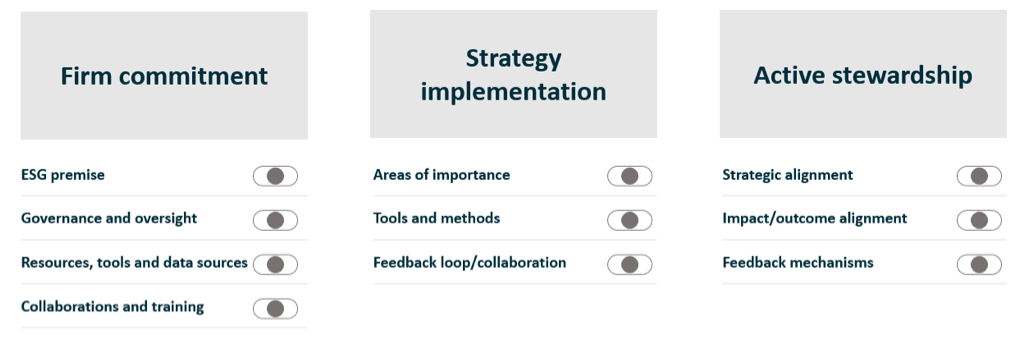

Source: Bloomberg Finance LP, as of March 13, 2021 Investment manager checklist – assessing managers on their firm commitment to ESG, their strategy implementation and active stewardship.

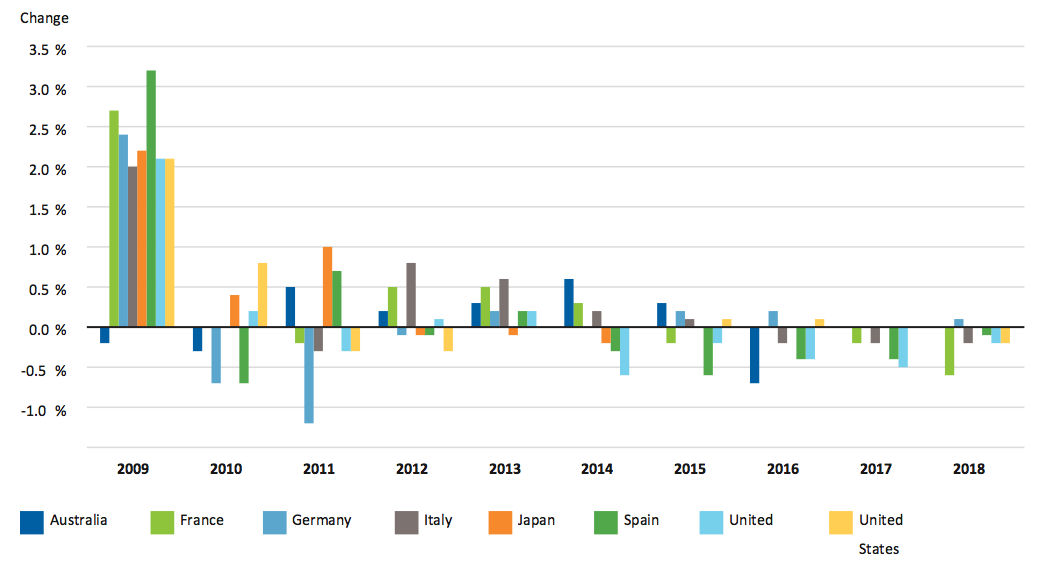

Investment manager checklist – assessing managers on their firm commitment to ESG, their strategy implementation and active stewardship. Sources: Franklin Templeton, OECD, Macrobond. As of November 2020.

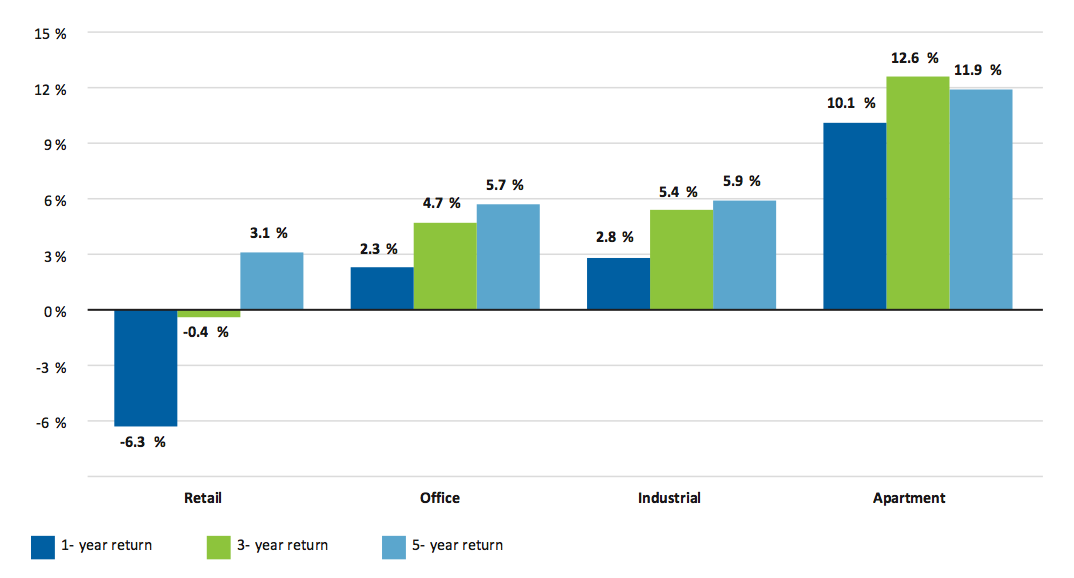

Sources: Franklin Templeton, OECD, Macrobond. As of November 2020. Sources: Franklin Templeton, NCREIF, Macrobond. Indexes are unmanaged, and one cannot invest directly in an index. They do not reflect any fees, expenses or sales charges. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

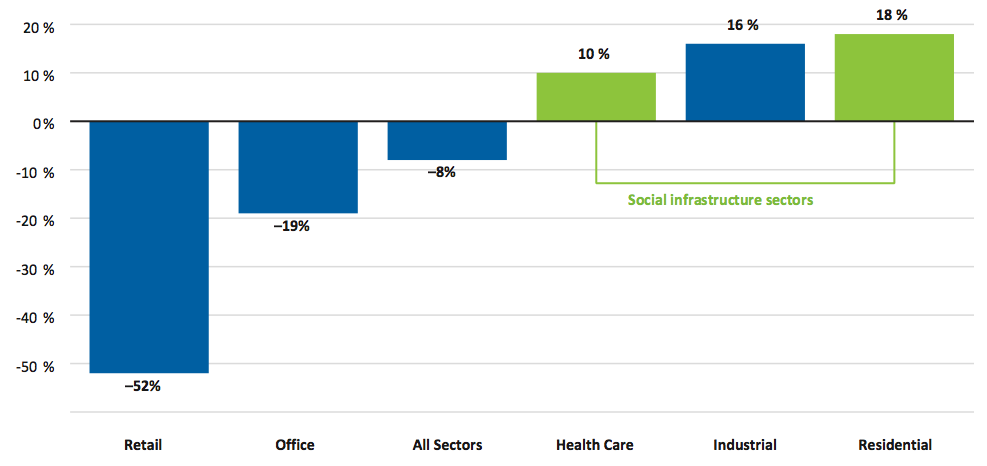

Sources: Franklin Templeton, NCREIF, Macrobond. Indexes are unmanaged, and one cannot invest directly in an index. They do not reflect any fees, expenses or sales charges. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance. Source: BNP Research. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.

Source: BNP Research. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future performance.