“He found a glimmer of hope in the ruins of disaster” ― Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on people and societies. In the world of investments, we see a silver lining in the opportunity for corporations to distinguish themselves through their support for various stakeholders, going beyond shareholders, to create long-term value. Capital markets have not been immune to the pandemic, with extreme levels of economic activity, unprecedented financial liquidity and divergence of the realities on “Main Street” and “Wall Street”. To better understand corporate responses to the pandemic, we engaged with our portfolio companies in March and April on three topics:

- Financial resilience and liquidity

- Initiatives to deal with the acute impact of the pandemic

- Long-term risks and opportunities

This article highlights our analysis on a sample of our portfolio companies to explore their support of different stakeholders, the potential relationship with short-term price performance and their ability to create longer-term value. Broadly speaking, we have concluded that our portfolio companies that took a focused and substantial approach to supporting key stakeholders have fared better during the pandemic and exhibit a positive bias towards higher long-term historical returns.

Who are the stakeholders?

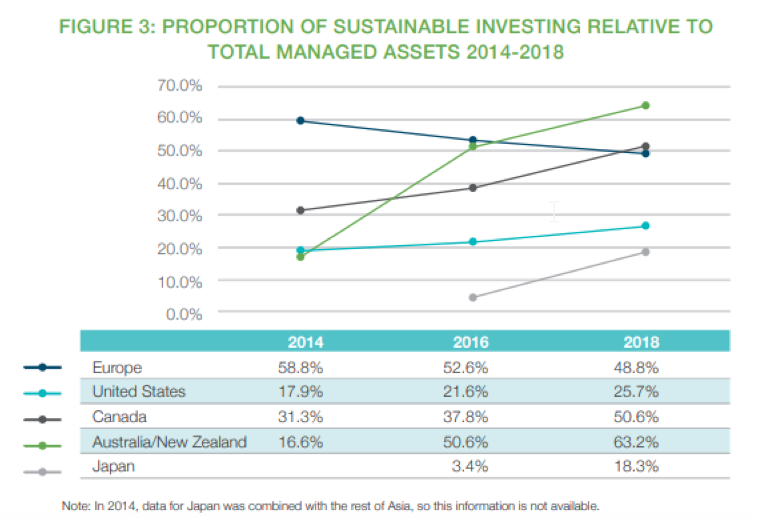

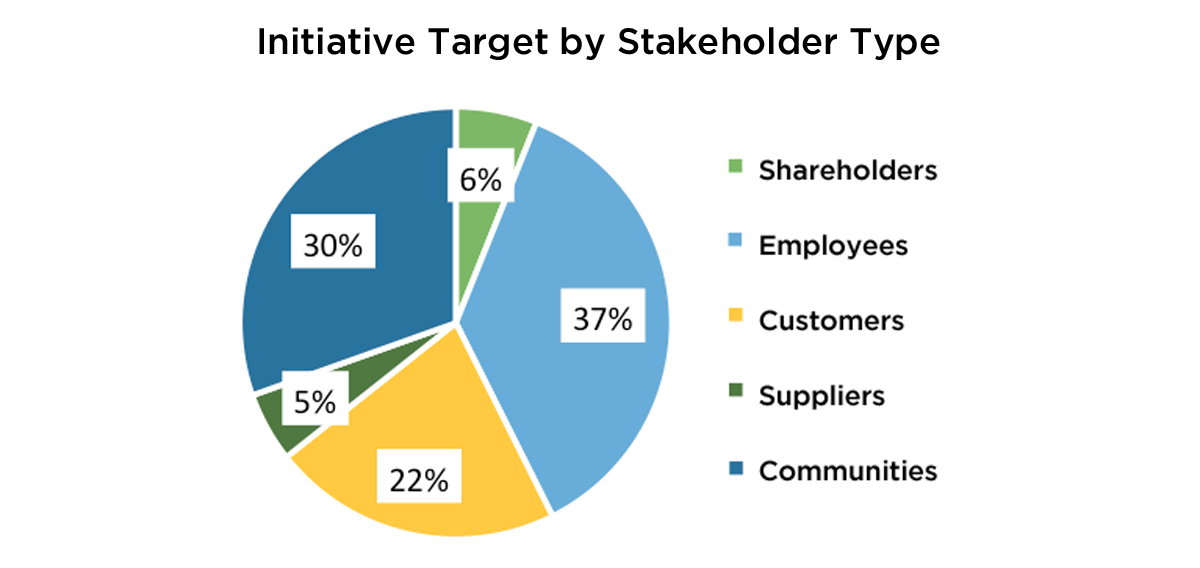

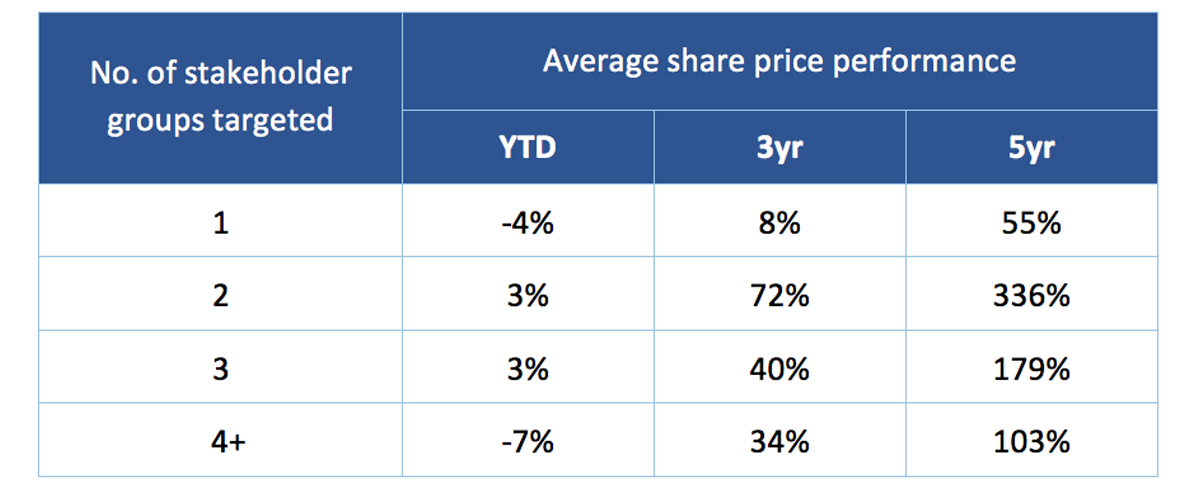

Our sample of initial efforts by companies from across our portfolios (Exhibit 1) found that the most frequently targeted stakeholder groups were Employees and Communities. There appeared to be a clear performance boost for taking an ambitious approach that targeted more than one stakeholder group, but this diminishes as more stakeholder groups were targeted (Exhibit 2). We believe that this suggests that substantial investments focused on material stakeholders had a more positive financial impact than efforts that defined stakeholders too narrowly or spread resources too broadly. We do recognize that other factors could affect the lack of linear relationship, including industry effects (banks having poor initial performance and some technology companies having extremely positive performance), and the greater impact of outliers in the smaller number of companies in our sample targeting four or more stakeholder groups.

Exhibit 1: Stakeholders targeted with Pandemic initiatives

Exhibit 2: # of Stakeholder groups targeted and average share price performance as of August 28, 2020

What were the initiatives?

Within each stakeholder category, companies took a wide range of approaches. For employees, responses ranged from providing danger pay, telecommuting options, and enhanced hygiene and sick leave practices to committing to pay laid-off employees in full. Support for suppliers included priority payments to small businesses, pausing loan payments and providing early payments to help with liquidity, while companies targeted communities through donations and working with governments, non-profits and hospitals. Most initiatives required investment of increasingly constrained corporate resources. For some companies, this meant decreasing capital targeted at shareholders (buybacks and dividends) or executives (compensation) in order to fund investments in other stakeholders. We assess these decisions similarly to any capital allocation decision and believe that the reductions in shareholder distributions were sound long-term strategies that can decrease both systemic and idiosyncratic risks for investors and create more opportunities for long-term value creation.

Simply put, as economic activity resumes, a business that has supported key employees, customers, suppliers and communities is more likely to emerge from the pandemic with the engaged workforce, loyal customers and resilient supply chains needed to restart their normal business activity and capitalize on emerging opportunities.

Looking Ahead to Resilience and Recovery

Months in, while COVID-19’s negative impact on people and economies has been deep and broad, it has disproportionately affected the disadvantaged. A robust, sustainable recovery will likely require both governments and the private sector to tackle this inequitable distribution of adverse effects. Periods of crisis present both risks and opportunities for investors. Of course, the risk exists that companies are not as resilient as believed or that the future environment is not as supportive of their activities. In cases where the impact is broad-based, there is also the systemic risk it poses to the markets in that functioning capital markets require a properly functioning economy and society.

The biggest opportunity of these rare but impactful events (other than deep dislocations in value) is the ability to observe the resilience and culture of companies as they react to the extreme uncertainty. The observations are part of an ongoing iterative process to refine our selection and research process to improve long-term risk-adjusted returns. Key learnings so far include:

- Rise of “S”: Companies and investors have emphasized social factors to address the deeper impact of the pandemic on employees, customers, suppliers and communities.

- Stakeholders beyond just shareholders: A healthy ecosystem of core stakeholders and financial prudence will benefit long-term shareholders by preserving the value of the existing business and positioning companies for a successful recovery and emerging opportunities.

- Resource/Capital allocation is key: Companies that focus their resources on initiatives more deeply aligned with their long-term value creation model are more likely to produce better results for shareholders. Having the culture, people, policy and capacity to make these difficult decisions and to balance different stakeholders is a key characteristic of successful long-term investments.

Going forward, there is still much uncertainty around the timing and nature of the eventual recovery. However, we continue to expect that companies that take a financially prudent approach to supporting key stakeholders will be the best positioned to create long-term value. As investors that look beyond the next year and even next decade, our job is to observe, learn and adjust course as necessary, while using our voice as active investors to encourage our portfolio companies to do the same.

Acknowledgement: This work would not have been possible without the help of Heather Sharpe, Eira Ong, and the entire JFL Research team.

RIA Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the Responsible Investment Association (RIA). The RIA does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee any of the claims made by the authors. This article is intended as general information and not investment advice. We recommend consulting with a qualified advisor or investment professional prior to making any investment or investment-related decision.

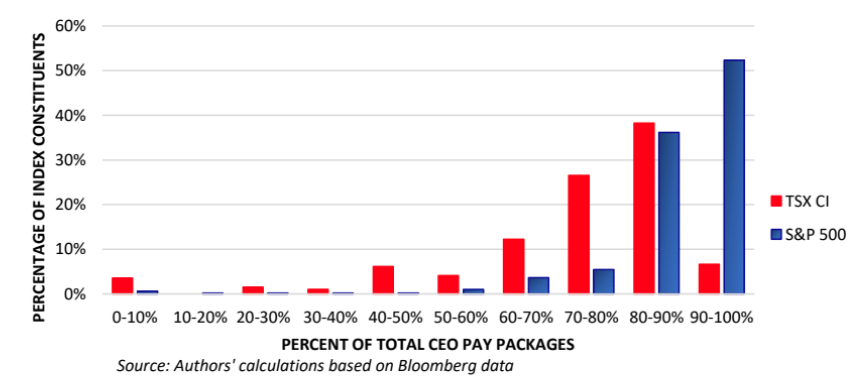

In reviewing executive compensation in 2019, NEI found base salaries in Canada did not exceed $2.5 million;[2] and in the U.S, they did not exceed US$5 million. And some CEOs, such as those at Facebook, Akamai Technologies Inc. and Prologis (all company founders) earned just one dollar in base salary.

In reviewing executive compensation in 2019, NEI found base salaries in Canada did not exceed $2.5 million;[2] and in the U.S, they did not exceed US$5 million. And some CEOs, such as those at Facebook, Akamai Technologies Inc. and Prologis (all company founders) earned just one dollar in base salary. As illustrated by the timeline, Shell engaged with shareholders throughout the process of establishing carbon goals and incorporating those goals into the executive incentive plans. Although some shareholder resolutions received relatively low support (~5%), they still put the pressure on Shell by emphasizing their focus on ESG.

As illustrated by the timeline, Shell engaged with shareholders throughout the process of establishing carbon goals and incorporating those goals into the executive incentive plans. Although some shareholder resolutions received relatively low support (~5%), they still put the pressure on Shell by emphasizing their focus on ESG.