If a key investment story of 2020 is COVID-19 and the disconnect between manic markets and a traumatized global economy, a less dramatic but financially urgent sequel to that story may focus on heightened market volatility and the search for more resilient investment solutions. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing has emerged as a key method for pursuing such portfolio resilience, particularly in the context of proliferating economic and systemic social risks.

ESG investing and the pandemic

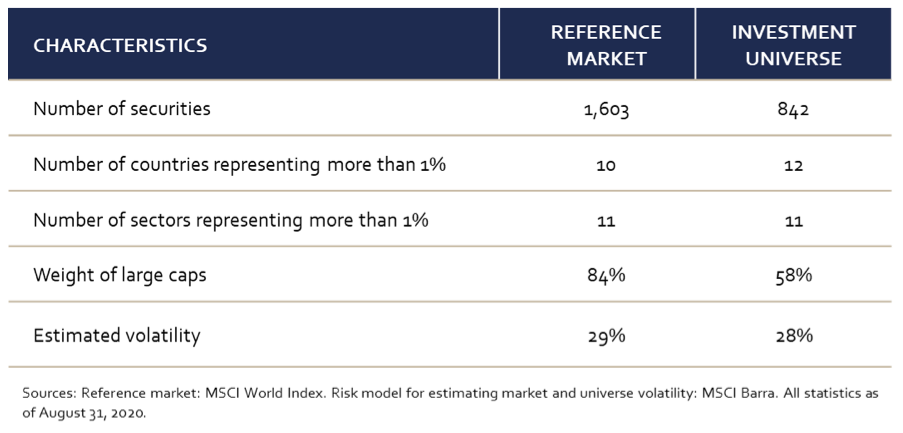

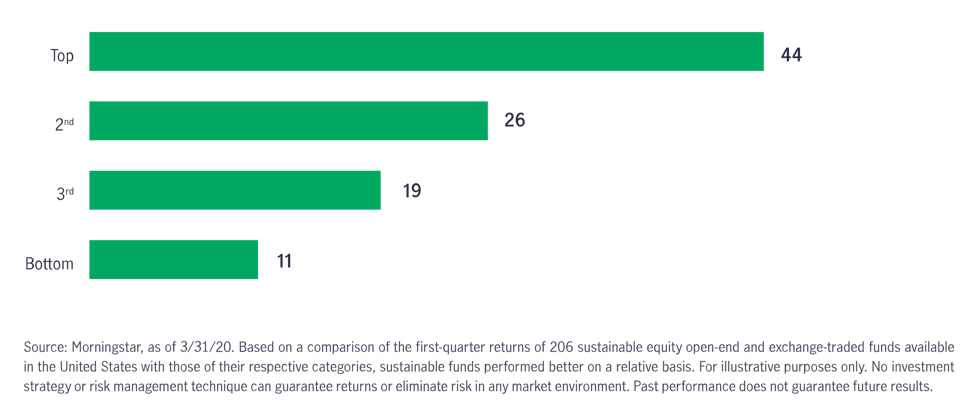

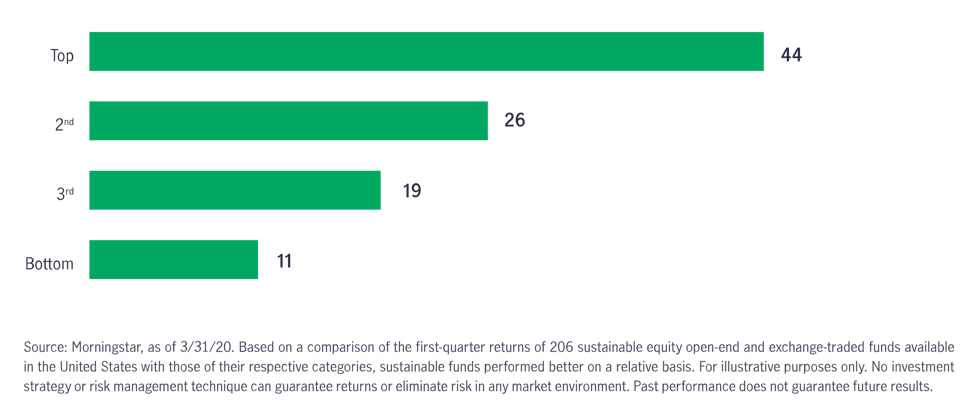

At the onset of this year’s pandemic-driven volatility, signals of ESG-related strength were widely noted, both at the company level and in ESG-focused equity investment strategies. For example, a Harvard Business School working paper released in April documented how companies that the public perceived as behaving more responsibly during the March downturn had less-negative stock returns than their competitors.[1] And in a widely cited U.S. mutual fund industry study, fund rating agency Morningstar remarked that “4 times more sustainable funds finishing in the best quartile than in the worst quartile of their categories” during the first quarter.[2]

Sustainable equity funds performed well during the crisis

Q1 2020 return rank % by Morningstar category quintile

What was the key to this resilience? One reason is a widespread energy sector underweight among ESG investment approaches. As COVID-19 dealt a serious blow to the near-term prospects for global economic growth, that helped trigger an oil price collapse and major volatility across the energy sector. A structural view against the future prospects of traditional energy companies, it appeared, helped the performance of a broad swath of ESG funds versus their traditionally managed peers.[3]

What was the key to this resilience? One reason is a widespread energy sector underweight among ESG investment approaches. As COVID-19 dealt a serious blow to the near-term prospects for global economic growth, that helped trigger an oil price collapse and major volatility across the energy sector. A structural view against the future prospects of traditional energy companies, it appeared, helped the performance of a broad swath of ESG funds versus their traditionally managed peers.[3]

Beyond the cautious sector view, the Wall Street Journal noted in late March that ESG factors, particularly social factors, could become more important at the corporate level as investor interest in companies’ approach to human capital management grew more urgent.[4] And as Morningstar’s Head of Sustainability Research for the Americas John Hale declared, ESG strategies appeared to be notably consistent outperformers because they tended to pursue the “quality companies of the 21st Century,” with a focus on “selecting stocks with better ESG credentials.”[5]

In this moment, ESG factors showed their close alliance—even an identity—with the most operative contemporary definitions of quality. Notably, though, this isn’t quality conceived as a history of profitability, but quality associated with a mix of quantitative and qualitative signals of sustainability, particularly factors that have often been called nonfinancial, intangible, or prefinancial.

In times of crisis, the prefinancial costs can become financial—sometimes, materially so—flipping the script of materiality and displacing other factors that might formerly have been deemed to have a greater impact on a company’s bottom line. One of the questions we face now concerns whether this reshuffling of factors on the basis of their materiality requires a tactical or a more strategic shift in investment approach.

The pandemic and the proliferation of social risks

As the pandemic has progressed, it appears that companies with a stronger ESG proposition seemed better prepared to weather the economic storm that no one projected would happen,[6] not to mention the social unrest that soon followed. Surfacing a range of systemic social risks, the pandemic has underscored the fragility of economic structures in relation to social factors.

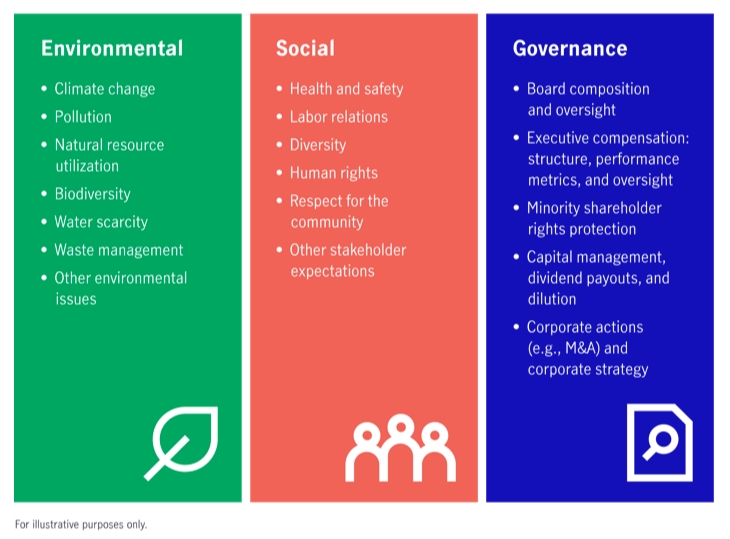

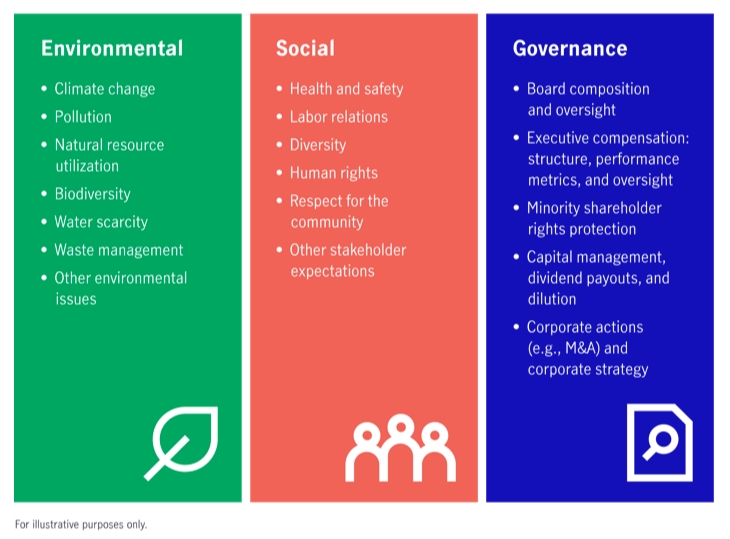

According to some observers, ESG strategies have maintained an edge through 2020’s market dislocations because they’ve taken a long view on what counts as a sustainable investment across sectors. Banks and other institutions that formerly downplayed the significance of ESG investing have consequently developed a keen interest in sustainable investment characteristics.[7] We think this set of key characteristics is a dynamic but finite set of interrelated ESG factors.

Some ESG factors that we believe are most relevant to our investments

An ESG strategy’s potential for outperformance, moreover, rests on its practice of modeling different scenarios of deterioration or strength. That can mean anticipating the consequences for corporate health in the context of varying climate scenarios or the degree of positive or negative momentum due to changes in social conditions. While the social factors at issue in the pandemic have varied by region and time frame, the social factors we’ve observed as being the most material for the greatest number of companies include health and safety, labor relations, and respect for the community.

Health and safety: public health structures under pressure

Health and safety are at the center of the pandemic’s swirl of uncertainty. In March, market participants of all levels of sophistication suddenly found themselves grappling with personal and community-focused health questions that could have profound consequences for their lives, livelihoods, and investment portfolios:

- Is it safe for anyone to go to work or for my children to go to school? How long will my family need to shelter in place?

- Is our public health system equipped to handle the pandemic or will it be pushed past its breaking point?

- Would resources aimed at finding a cure be allocated in a way that hastened the development of truly effective treatments for the general population or shareholder-and insider-focused profits?

There were and continue to be no guarantees that the resolution to these health and safety questions will be positive in the short to medium term, neither for the global population nor for the global economy. Faced with such staggering uncertainty, traditional asset managers and asset owners were all equally in the dark about what they could reasonably expect from their portfolios in the way of risk/adjusted returns. But because of their focus on systemic risks, ESG-strategies can be more aware of the materiality of social risks for different companies, industries, and economically interdependent regions exposed to outbreaks.

Labor relations: a major stress test for companies in hard-hit areas

At no time since the Great Depression did so many people lose their jobs or have the safety of their employment put into doubt so quickly. Consequently, labor relations swiftly became a flash point for companies across the capitalization spectrum:

- How steadfast could companies be in treating employees empathetically—putting their health and safety, not to mention their jobs, above corporate profits? What if the crisis wears on into 2021 and beyond?

- Would companies be able to create safe workspaces for their employees? At what cost?

- Were companies fully aware that their behavior during the crisis might define their future ability to retain talent and customer loyalty?

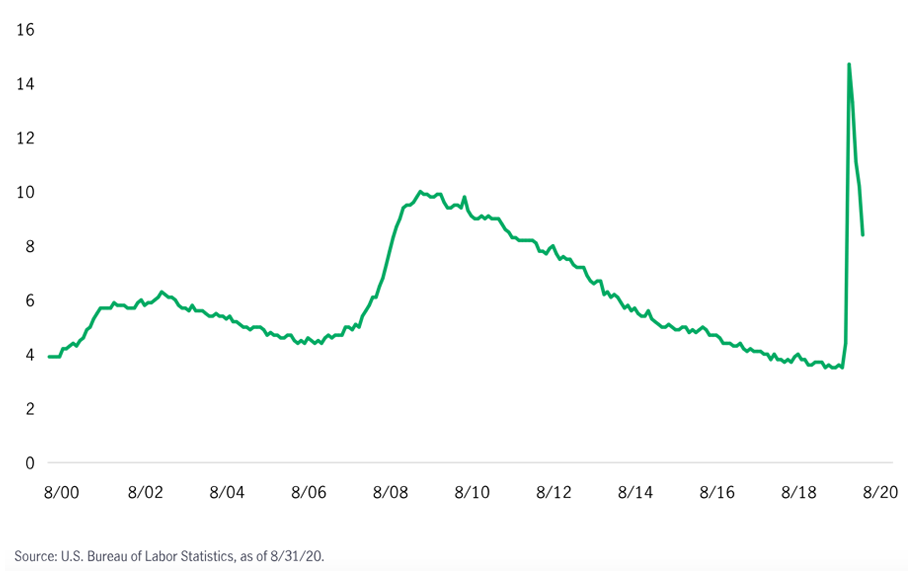

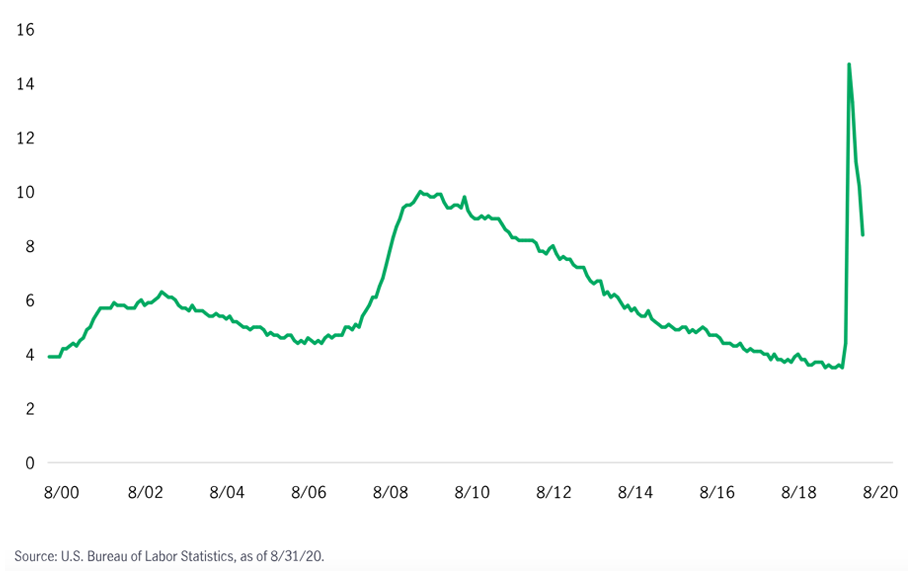

In the early stages of the first wave of the pandemic, charts showing unemployment data registered an implausibly sharp spike. Within a matter of weeks, U.S. unemployment rose above 14%, indicating tens of millions of people had lost their jobs. While data was more mixed in European countries, emerging economies also faced a severe employment shock.[8] What could companies and sovereigns realistically do to protect the unemployed and the still employed but quickly overextended essential workers? How companies treat their employees in the context of once-in-a-generation financial difficulty is perhaps the ultimate stress test measuring the relative strength of the social factor across companies, industries, and sectors.

U.S. Civilian unemployment rate (%)

August 2000-August 2020

Respect for the community: positive catalyst for change?

Respect for the community: positive catalyst for change?

Respect for the community has become another flash point of risk and opportunity for many companies since the onset of the crisis:

- Would companies take pains to shift their operations smoothly—for example, by implementing business continuity plans or by putting certain operations on hold until a time of relative safety?

- If a company operated in the presence of the general public, did it respect pandemic-mitigation measures or treat these in a more cavalier manner?

- Did companies donate resources to help the broader community? Whether that meant donating PPE gear or converting manufacturing capacity to build ventilators, produce hand sanitizer, and so on.

- In what ways have companies pledged to change for the long term, particularly with respect to how they see themselves and their operations having an impact on the communities in which they operate?

Many companies have shown a willingness to tread a path toward social change. Nowhere is this more evident than in the United States, where the pandemic has exacerbated tensions in the country’s ongoing reckoning over its history of racial injustice. Where companies stand on the relevant issues has more than occasionally had an impact on their business, and—on the hopeful side—these positions may become catalysts for improved results in U.S. board diversity, gender equality, and equitable compensation structures that favor broad stakeholder interests.

Sustainable investing is resilient investing

For ESG investors, the central focus is on sustainability, a condition of resiliency represented in company fundamentals and management effectiveness at managing material risks, which, in aggregate, gives companies a better chance of thriving in the future. As it was recently put in Responsible Investor, the measure of company’s sustainability comes down to “how resilient and agile [they are] in handling many stakeholders, global uncertainties, shocks and disruptions—regardless of whether these are caused by a pandemic, social unrest, or an environmental emergency.”[9]

Qualitative, prefinancial factors are accepted by ESG strategies as potential drivers of future business strength and weakness. That may be one reason why momentum continues to gather behind ESG strategies, as investors increasingly look to see whether a company has the strategic vision and capabilities to achieve and maintain strong ESG performance—in other words, long-term resiliency and the ability to manage tail risks.

Sources:

[1] “Corporate Resilience and Response During COVID-19,” Alex Cheema-Fox, Bridget LaPerla, George Serafeim, and Hui (Stacie) Wang, Harvard Business School Accounting & Management Unit Working Paper No. 20-108, April 2020.

[2] “Sustainable Funds Weather the First Quarter Better Than Conventional Funds,” Morningstar, April 3, 2020. The study is cited by interactive investor, “The reason why ESG funds outperformed during the market sell-off,” March 24, 2020, and CNBC.com, “The coronavirus downturn has highlighted a growing investment opportunity —and millennials love it,”April 14, 2020, among others.

[3] Morningstar, April 3, 2020.

[4] “Coronavirus Pandemic Could Elevate ESG Factors,” Wall Street Journal,March 25, 2020.

[5] Morningstar, April 3, 2020.

[6] Of course, numerous well-known public figures have spoken in the past about the likelihood—even the inevitability—of a pandemic wreaking havoc on the global economy. See, for example, Microsoft co-founder and philanthropist Bill Gates’s 2015 Ted Talk.

[7] Wall Street Journal, March 25, 2020.

[8] “Emerging economies in full-blown unemployment crisis,” United Nations, June 4, 2020.

[9] “No Surprise: Sustainability Funds Outperform the Market—Despite COVID-19,” Responsible Investor, April 24, 2020.

Contributor Disclaimer

A widespread health crisis such as a global pandemic could cause substantial market volatility, exchange trading suspensions, and closures, and affect portfolio performance. For example, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has resulted in significant disruptions to global business activity. The impact of a health crisis and other epidemics and pandemics that may arise in the future, could affect the global economy in ways that cannot necessarily be foreseen at the present time. A health crisis may exacerbate other pre-existing political, social and economic risks. Any such impact could adversely affect the portfolio’s performance, resulting in losses to your investment.

The opinions expressed are those of Manulife Investment Management as of the date of this publication, and are subject to change based on market and other conditions. The information and/or analysis contained in this material have been compiled or arrived at from sources believed to be reliable but Manulife Investment Management does not make any representation as to their accuracy, correctness, usefulness or completeness and does not accept liability for any loss arising from the use hereof or the information and/or analysis contained herein. Manulife Investment Management disclaims any responsibility to update such information. Neither Manulife Investment Management or its affiliates, nor any of their directors, officers or employees shall assume any liability or responsibility for any direct or indirect loss or damage or any other consequence of any person acting or not acting in reliance on the information contained herein.

All overviews and commentary are intended to be general in nature and for current interest. While helpful, these overviews are no substitute for professional tax, investment or legal advice. Clients should seek professional advice for their particular situation. Neither Manulife, Manulife Investment Management Limited, Manulife Investment Management, nor any of their affiliates or representatives is providing tax, investment or legal advice. Past performance does not guarantee future results. This material was prepared solely for informational purposes, does not constitute an offer or an invitation by or on behalf of Manulife Investment Management to any person to buy or sell any security and is no indication of trading intent in any fund or account managed by Manulife Investment Management. No investment strategy or risk management technique can guarantee returns or eliminate risk in any market environment. Unless otherwise specified, all data is sourced from Manulife Investment Management.

Manulife, Manulife Investment Management, the Stylized M Design, and Manulife Investment Management & Stylized M Design are trademarks of The Manufacturers Life Insurance Company and are used by it, and by its affiliates under license.

RIA Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view or position of the Responsible Investment Association (RIA). The RIA does not endorse, recommend, or guarantee any of the claims made by the authors. This article is intended as general information and not investment advice. We recommend consulting with a qualified advisor or investment professional prior to making any investment or investment-related decision.

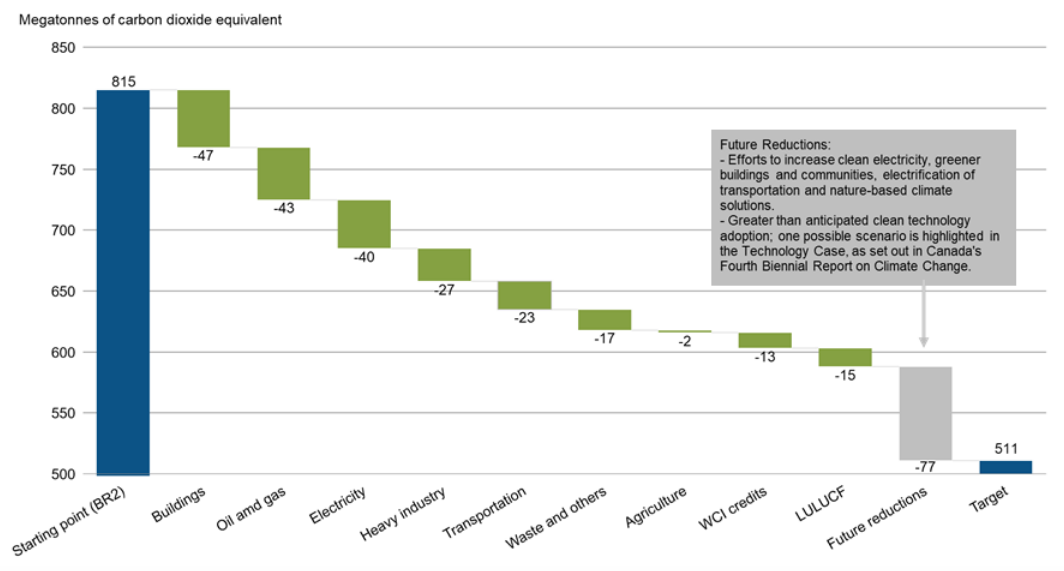

Source: Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change: Progress Towards Canada’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2019

Source: Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change: Progress Towards Canada’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions, 2019

What was the key to this resilience? One reason is a widespread energy sector underweight among ESG investment approaches. As COVID-19 dealt a serious blow to the near-term prospects for global economic growth, that helped trigger an oil price collapse and major volatility across the energy sector. A structural view against the future prospects of traditional energy companies, it appeared, helped the performance of a broad swath of ESG funds versus their traditionally managed peers.[3]

What was the key to this resilience? One reason is a widespread energy sector underweight among ESG investment approaches. As COVID-19 dealt a serious blow to the near-term prospects for global economic growth, that helped trigger an oil price collapse and major volatility across the energy sector. A structural view against the future prospects of traditional energy companies, it appeared, helped the performance of a broad swath of ESG funds versus their traditionally managed peers.[3]

Respect for the community: positive catalyst for change?

Respect for the community: positive catalyst for change?