There have been encouraging changes in the impact investing market as it matures, with asset owners and fund managers now paying more attention to the ‘Social’ or ‘S’ in ESG, expanding from the initial more limited focus on environmental sustainability (the ‘E’).

One social issue which intersects both social and environment categories and has taken on increasing pan Canadian prominence is the structural undersupply of affordable housing. The need for more affordable housing has been well documented in Canada, with housing 34 percent more expensive than median income household earnings and the largest cities in Canada topping the list of the least affordable in North America. Less firmly articulated have been tangible solutions, and specifically the imperative role of private capital, in tackling the housing crisis.

A growing market

This is a global issue, not just a Canadian one, and what we can learn from looking abroad is that impact investing is a critical part of the solution. There’s a significant need for private capital to help respond to this supply shortage through both debt and equity models.

Investor interest is expanding, and capital is beginning to flow at pace in other parts of the world. For example, investment into affordable housing funds has been the largest contributor to the growth of the social impact investment market in the UK, making up 42% of the market which is estimated to be worth £5.1 billion ($6.7 billion). Many of the funds emerging provide equity-like finance to acquire or develop properties through lease-based structures. This is one part of the solution to the UK’s housing affordability problem where there is a housing shortage of 60,000 homes/year and where, like Canada, home prices have soared in recent years.

Financing from UK government agencies, as co-investors in the funds rather than simply their traditional grant funding role, has been a helpful signal of support as the UK market matures. The fund management landscape is also evolving; fund managers, once specialist impact managers, now include some of the leading global asset managers, launching funds to provide affordable and specialist housing as well as housing to address homelessness, many with aspirations of raising hundreds of millions.

The amount of institutional investment flowing into this sector is due to the strong financial case for affordable housing funds: portfolio diversification, long-term index-linked income, combined with the significant demand for private capital.

What are we seeing in Canada?

CMHC has the ‘aspirational goal’ of eliminating housing need by 2030. While efforts have increased towards this end, for example CMHC’s Affordable Housing Innovation Fund and New Market Funds’ own affordable housing funds, we are only now starting to see the investor appetite in Canada that has emerged in the UK, despite a similar scope of problem and opportunity set.

Impact investment into affordable housing in Canada is of course not new, but there remain few funds that commit to delivering affordable housing in perpetuity based on community needs, working in partnership with local housing stakeholders. This community partnership approach is essential to investing in housing which works over the long-term.

Barriers to scaling up impact investment into affordable housing in Canada

Most ‘affordable housing’ in Canada is provided via mandates to private developers as part of larger, market-rate developments. The types of housing delivered through these developments is often limited to smaller, one-bedroom and studio units, unsuitable for the many families in need of affordable homes.

Additionally, the tenure length where affordability is limited to 10-20 years is inadequate because once that initial period expires, the housing often reverts to market rate, leading to security of tenure issues and impact loss over time. To make a sustainable impact, affordability should ideally be in perpetuity, built into lease and partnership agreements from the outset.

What we mean by ‘affordable’ also needs to be refined. While the standard definition links affordable rents to market rents, with growth of market rents consistently outpacing growth of incomes, affordability decreases over time. A more appropriate measure of affordability would be income-based, setting affordable rents at a maximum proportion of median net household incomes, adjusted for geography and number of bedrooms.

Lastly, there are secondary issues like housing investment activity inflating property valuations, unintentionally pricing out the beneficiaries that investors like public pension plans serve. These negative impacts need to be better understood and reported on as the sector grows.

Many of the above challenges are not unique to Canada. We can again look to social investment markets that have had a head start to avoid pitfalls and ensure that as the market here continues to grow, quality and suitability of the housing being delivered, and impact integrity, are at its core.

Standardizing impact management approaches

Accompanying the rapid market growth in the UK has been questions and inconsistencies about the way that impact is measured, monitored and reported. While many fund managers and housing providers have developed positive partnerships, there is not always transparency around the risk and return characteristics of investments or honesty about the impact additionality – that is, the actual impact that is achieved – from any given investment.

One initiative recently launched in the UK to help tackle these issues brought together leading fund managers to develop a common impact reporting approach for equity investment into affordable housing. The purpose of the project is to set common reporting standards, mitigate negative risks, and encourage investment flows that make a positive difference on the supply and quality of affordable housing over the long term.

As the Canadian market evolves, similar ground rules will need to be established to set standards and ensure that incentives are aligned. This will help investors better navigate the social investment market and assess good opportunities from bad, encouraging as much capital as possible to flow towards delivering the genuinely affordable housing Canada so urgently needs.

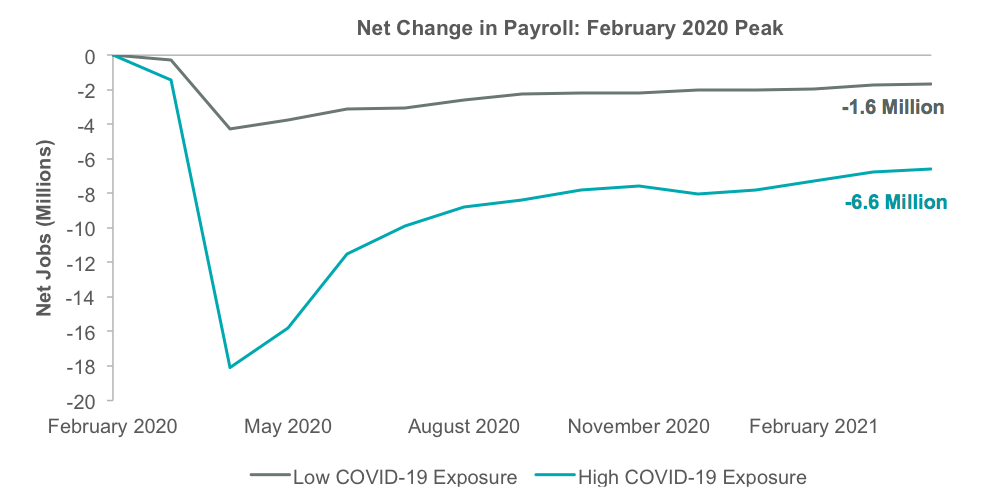

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford

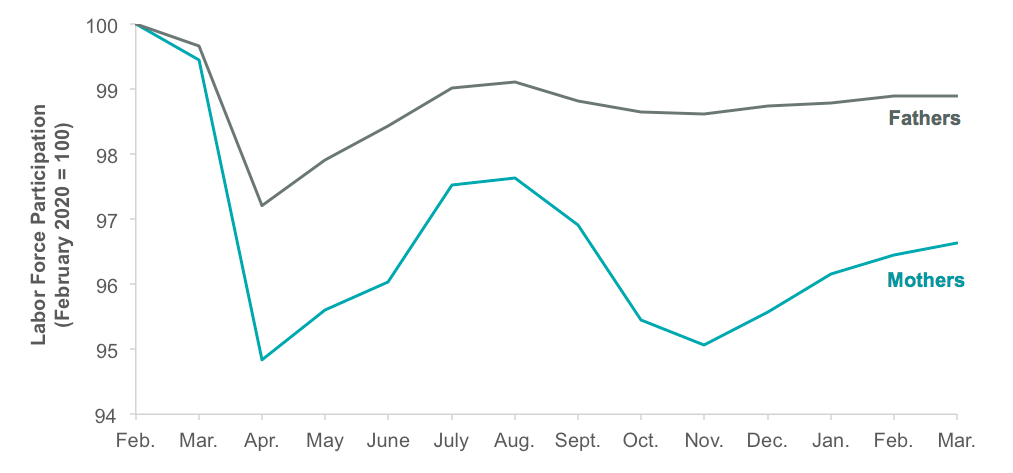

High and low COVID-19 exposure is based on industry-level data measuring data including the ability to work remotely, essential vs. non-essential status, and supply/demand shocks resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Aggregate net change in payroll employment in these industries is measured relative to February 2020 peak employment levels. High COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~60% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment; Low COVID-19 exposure industries account for ~40% of pre-pandemic total non-farm payroll employment. Data as of April 30, 2021. Source: Bloomberg, BLS, INET Oxford Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

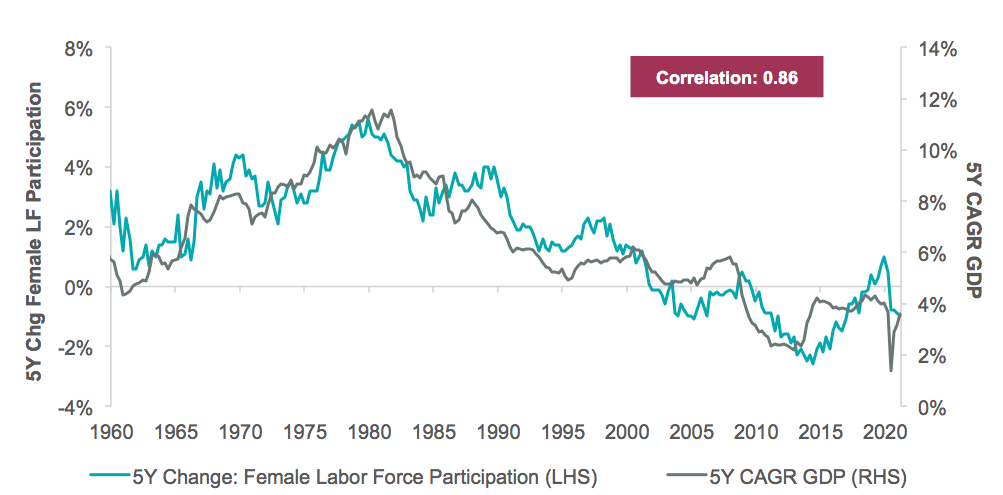

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.

Data as of March 31, 2021. Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bloomberg.